In the quiet of February 1846, in the sleepy farming village of Canova on the banks of the Rio Grande, Maria Rosa Gonzalez (age 26), the wife of Jose Maria Esquibel (age 29), gave birth to a baby girl later baptized as Maria Eulalita Esquivel.

While she was still at her mother’s breast, the world around her family changed. American troops marched from Kansas across the Great Plains the following summer, taking over militarily their remote Mexican territory in a time of war. As a toddler, she might have even heard the gunfire exchanged between American soldiers sent to dislodge the Taos Mexican rebel defenses at the Battle of Embudo Pass, just on the other side of La Joya (a village later renamed Velarde), located across the river from their home.

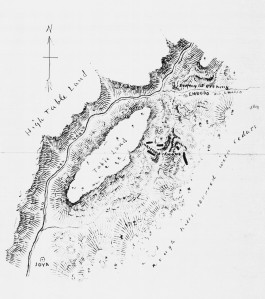

When the dust from America’s Annexation of New Mexico settled, Eulalita grew up quietly in her remote Hispanic community a few miles upstream from the bigger settlement of San Juan de los Caballeros. This mostly Tewa Pueblo community, which only recently readopting its original name of Ohkay Owingeh, dominated this part of the Rio Arriba, or upper river country. For young Eulalita, the sun rose above the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the east, and set behind the mesas that marked the edge of the Rio Grande valley in the west. Her childhood could reasonably be expected to have been tranquil, secure from many of the changes that New Mexico’s Hispanic culture eventually faced.

But as changes enveloped the girl as her teen years rapidly approached, so too were changes enveloping New Mexico (a vast territory stretching from Texas to California, bounded in the north by Colorado Mormon Utah). Beyond the Sangre de Cristo and the staked plains that divided this little world from the politics of the eastern coast of the country, national leaders began a great Civil War, a contest fought over the rights of individual states to determine their own course, and the will of the country’s national leadership to ensure social progress. New Mexico politicians tried their best to sense the way that the wind was blowing from Washington, D.C., where most of the decisions on the newly annexed territories were made. Ultimately, the territory split between north and south, with all lands south of Socorro becoming part of the territory of Confederate Arizona, which fell to the Union after Henry Hopkins Sibley’s failed attempt to sieze the Mint at Denver.

Well out of the way of the fighting at Glorieta Pass and Valverde, Eulalita continued to help around their family’s little farm. The last of her parent’s five children, Maria Juana, came into this world at the time that the fighting started. By the time that peace was restored back east, the young woman would have no doubt been more than ready to build a family of her own with a suitable young man.

José Miguel Rodríguez Roybal, a member of Santos Rodríguez’s family of six boys and three girls, came down from his homestead in Embudo and carried her off into the hills north of La Joya after marrying her on Nov. 27, 1869. A month later on Christmas Eve, the couple celebrated the birth of Maria Josefa, their first child. A decade later, when Miguel disappeared from the scene, their family would include three girls and one boy.

New Mexico, meanwhile, accelerated in its transformation. At the end of the Civil War, the Navajo were rounded up and sent westward into the newly formed Arizona Territory (divided from New Mexico at the fall of the Confederacy at the 109th parallel, the present border), ending raids on livestock along the Rio Grande. In Santa Fe, Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy continued the work he had started before the War, to build chapels and cathedrals across his diocese as new pilgrimage sites sprang up next to older ones (as at nearby Chimayo). As Hispanic farmers, the Rodriguez Roybal family really did live in a Land of Enchantment.

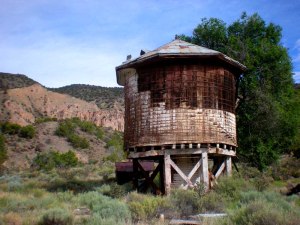

Denver and Rio Grand Railway Engine No. 220 at Embudo Station. Photo by Otto C. Perry via Denver Public Library and Wikimedia Commons

Then, around the time that the Santa Fe railroad connected Raton Pass with Kansas, Miguel disappeared from the scene at Embudo, leaving Eulalita with her four children. Left vulnerable by the loss of a husband, according to family legend, she had begun to see an unknown Tewa man from San Juan de los Caballeros. The result of that liaison was a girl named Cirila, my family’s direct ancestor, born around the start of 1880. As with Miguel before him, the Tewa man disappeared as well, leaving Eulalita a single mother in her 30s.

Meanwhile, the arrival of the railroads triggered massive changes to the region, and not just along the Santa Fe Railway. From Denver, a second consortium, the Denver and Rio Grande, sought to build a train line from Colorado all the way down to Mexico City. The defeat in the fight for access to Raton Pass prompted the D&RG to extend their tracks south of Alamosa instead, through Conejos and Tres Piedras on the way to the Rio Grande Gorge that runs between Taos and the newly opened Velarde Post Office. This so-called Chili Line transformed places like Embudo (soon renamed Dixon), which suddenly had a station through which the latest in manufactured goods could arrive. The end of the line turned the village of Espanola, near Santa Cruz de la Cañada, into a major hub. And it brought plenty of work for the young men in the region.

Water tower along the old Chili Line at Embudo Station. Photo by Einar Einarsson Kvaran, Librarian at the Embudo Valley Library, via Wikimedia Commons

Sometime around her 40th birthday, Eulalita met one such young Embudo-area man named Jose Nemesio Rendon, who was about 18 years her junior. Despite the age difference, the two fell in love and on Oct. 25, 1886, they married at San Juan de los Caballeros, at the time only a short distance from the new train station at Alcalde. And, oddly enough, Eulalita continued to bear children, providing a daughter and three sons before menapause finished her childbearing years sometime after her 45th birthday in the 1890s.

When the last child was born, Nemesio and Eulalita were caring for two 15-year-old twin girls by her first marriage (Nemesio was only about 12 years older than them) named Perfecta and Virginia, an 11-year-old daughter by the unknown Tewa man named Cirila, and Nemesio’s own children: Victoriana and Ignacio (twins, age 4), Tomas (age 3), and infant Manuel. Among the girls, the first to leave the nest was Perfecta, who on Nov. 12, 1896 married Pablo Martinez. Their marriage lasted at least five years, during which time her 18-year-old sister Cirila managed to get into trouble with a young man, resulting in the birth of Juan Jose Lauro Vernavey Rendon (more simply known as Lauro, or Larry). Cirila was fortunate enough to meet another man named Elias Valdez, who fell in love and married her a couple years later on Nov. 30, 1901 (Lauro, whom his step-sister Alvina regarded as particularly handsome, was apparently raised by his grandmother, who by the date that he registered for the draft in World War I apparently regarded Eulalita as more his own mother than Cirila).

On Apr. 7, 1902, Victoriana married at age 15 a man 10 years older than her named Tobias Cordova. Tobias was the son of a woman who lived a number of years as the single mother of three children, quite possibly by three different men, named Teresa Cordova. Daughter of one of Truchas’ most famous Spanish pioneer families, she later married Jose Blas Maes, by whom she had five more children. The eldest of these turned out to be one of the family’s more notorious characters, Maximiliano Maes, who Virginia Roybal married on July 12, 1909. Cirila’s daughter, Alvina (my grandmother), told in an interview before her death in the 1990s that Maximiliano made quite a bit of money in the early part of the century by making moonshine and growing marijuana in the hills above Velarde.

Perfecta, meanwhile remarried on May 19, 1913, to Pablin Gasco, and like pretty much of the rest of the family, led somewhat less risky, perhaps boring, lives as law-abiding citizens along the Low Road to Taos. And that was probably her most resounding legacy that Eulalita left her family, that through times of troubles, she ensured that the majority of her children found productive places in modern New Mexico society.

Pingback: Another late Father’s Day ancestry: On the road to Moctezuma | BenStuff

Pingback: Another late Father’s Day ancestry: On the road to Moctezuma | BenStuff

I think we’re related 🙂 My Grandfather was the handsome Lauro Rendon 🙂